Pictish power and culture

© National Galleries of Scotland

Pictish power and culture

Cumhachd is cultar nan Cruithneach

At the centre, not the edge

Sa mheadhan, chan ann air an iomall

The centre of the Pictish kingdom was long assumed to be south of the Highlands in the territory of southern Pictland. But recent research and a revived interest in the Picts now suggests the Highlands were at the centre of Pictish power and culture, and to have been at the core. This region appears to have been the core of the Pictish kingdom at its most powerful period, placing the northern Picts firmly at the centre, not the edge.

Urquhart Castle

Craig Phadrig

Tarbat Discovery Centre

The Shandwick Stone

The Red Priest's Stone

The Lybster Stone

Tarbat Discovery Centre

The Shandwick Stone

The Nigg Stone

The Hilton of Cadboll Stone

Kyle of Sutherland Heritage Centre

Dunrobin Castle Museum

Missionaries and monasteries

Miseanaraidhean is manachainnean

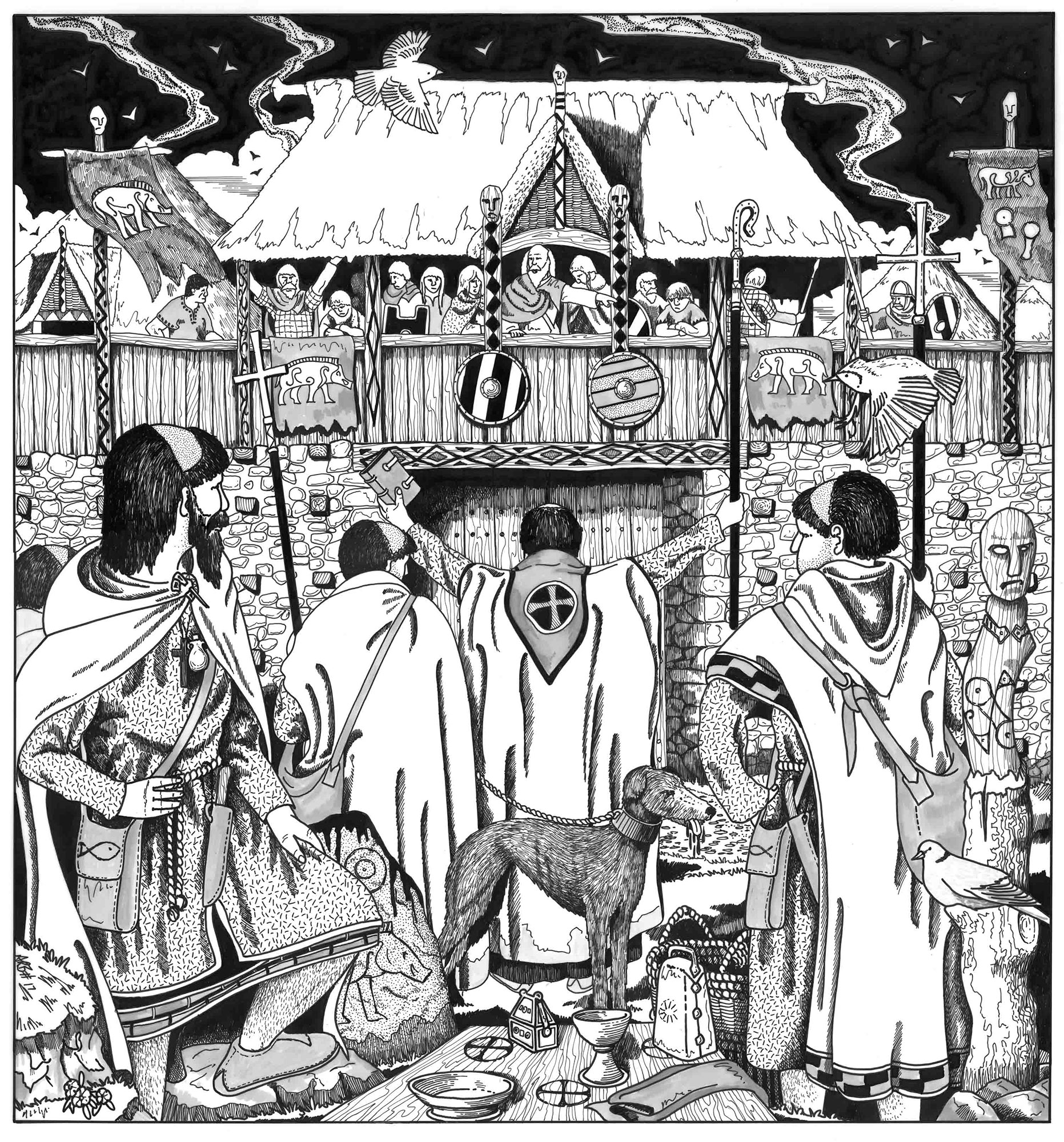

There may have been small numbers of Christian Picts from the fifth century AD due to the influence of Romano-Britons from the south of what is now Scotland. Christianity began to spread further in Pictland during the sixth century. Connections between the Church in Pictland with Ireland and the west coast of Scotland were important from an early stage.

He settled on the island of Iona on the west coast of Scotland in around 563 AD. According to Columba’s biographer Adomnán, Columba travelled the Great Glen including along Loch Ness. It is possible he stopped at the site where Urquhart Castle now sits. Adomnán also tells of the saint’s encounter with a monster in the River Ness. Adomnán suggests Columba met the Pictish king Bridei somewhere near Inverness. The hill fort of Craig Phadrig is a likely location. It is not clear that Columba directly converted any of these northern Picts to Christianity, but perhaps small monastic communities were founded in the Highlands in Columba’s time. Increased research and archaeological investigation have shown the significance of sites across the Highlands including the monastery at Applecross founded by the Irish Saint Maelrubha in 671 AD. Rosemarkie and Portmahomack in Easter Ross were also important Christian centres.

Christian centres of power

Àiteachan cumhachdach Crìosdail

Archaeological excavations over the past twenty years at Portmahomack on the Easter Ross (Tarbat) Peninsula, have transformed our understanding of the Picts in the north. The resulting discoveries on display at Tarbat Discovery Centre show the significance of the religious power and influence here in Easter Ross.

Pieces of Pictish carved stone were first unearthed on this site in the 1800s by church gravediggers. In 1984 an aerial survey highlighted a buried ditch around the church, similar in shape to the enclosure of St Columba’s monastery in Iona. This led to a nearly twenty-year project with Dr Martin Carver and his team from University of York. Their work has yielded sensational results and helped to overturn established thinking about the Picts.

Over two hundred burials have been recorded on the site, including nearly seventy graves containing the remains of mainly middle-aged or elderly men radiocarbon dated to the 500s AD. These were distinctive Pictish ‘cist’ burials – graves wholly or partly lined with stone slabs.

In addition, many pieces of carved stone dating to the 700s AD were found in the foundations of the later medieval church – with more than 150 carved stones since recovered from excavations. Many are simple gravemarkers similar to those found in Iona and around the Highlands in places such as Strathnaver. One massive slab with a lion and wild boar belongs to a sarcophagus lid or maybe an altar, and many of the stone fragments come from one or more monumental cross slabs like the Nigg Stone or the Shandwick Stone.

Excavations around the church showed the extent of the early Christian monastery. A workshop area revealed evidence of silver and bronze making, moulds, leather, bone and wood fragments. Sometime during 800 AD the workshop area was destroyed by fire and all the cross slabs were broken up and dumped. It seems likely that this targeted attack was the work of the Vikings.

The magnificent collection of Pictish sculpture now on display at Groam House Museum illuminates Rosemarkie as another major centre of religion in the north. Historical sources tell us of Curetan (later Saint Curetan) a late seventh century bishop who was based here. Curetan was probably a Pict and possibly a native of Ross-shire. The Northumbrian monk Bede recorded that in 710AD the Pictish king Nechtan sent a request to his abbot to send monks and masons to assist in building a stone church in the Roman style. Nechtan also ordered that his kingdom should celebrate Easter according to the rules used by the Roman rather than the Irish Church. This command went out to all the provinces of the Picts, to be copied, learned and adopted. This copying could only have taken place at a monastery, as only the monks could read and write. It is quite possible that Nechtan’s decree was recorded either at Rosemarkie or Portmahomack before being sent further afield.

The Pictish monastery at Rosemarkie must have had strong political links with the Pictish royal centre of Burghead and its nearby monastic centre of Kinnedar both on the Moray coast. It was only a short sea crossing to the south side of the Moray Firth and then eastwards to Burghead. Rosemarkie would also have had strong religious links with the Easter Ross (Tarbat) Peninsula and the monastery at Portmahomack with its outlying sites marked by the impressive Pictish cross slabs of the Hilton of Cadboll stone, the Shandwick Stone and The Nigg Stone.

By 800 AD the whole East Ross (Tarbat) Peninsula had emerged as a major ecclesiastical centre. Its boundaries are marked by monumental cross slabs carrying some of the most complex iconography seen in early Christian art. That it was destroyed by the Vikings so soon afterwards is a sombre thought.

A cultural powerhouse

Àite cumhachdach a thaobh cultair

The huge cultural influence of the Christian Church brought Pictland into the mainstream of European art and civilisation. The visual images and symbols on many of the Pictish cross slabs across the Highlands – for example the Kincardine Gravemarker (Kyle of Sutherland Heritage Centre) and the Shandwick Stone – show that this was a society immersed in the European biblical scholarship of the times. The Nigg Stone has artistic elements also seen in sculpture from Iona and St Andrews in Fife, and the stylistic links between the Book of Kells and Pictish stone carving is clear in examples at Applecross Heritage Centre, Rosemarkie, Tarbat Discovery Centre and the Golspie stone at Dunrobin Castle Museum.

All of this indicates that the Highland area was not a backwater but rather a culture engaging with the Christian culture of the time by displaying or interpreting it on the huge monuments that can still be seen in the Highland landscape today. Pictish kings also used biblical imagery to stamp their patronage or authority on a site – for example, historians have argued that the inclusion of images of the biblical David on sculpture such as the Nigg Stone and the Kincardine Gravemarker is evidence of the influence on these sites of powerful Pictish kings in the 700s AD.