Art of the Picts

Art of the Picts

Ealain nan Cruithneach

A lasting legacy of enigmatic art

Dìleab mhaireannach de ealain dìomhair

The Eagle Stone

Gairloch Museum

North Coast Visitor Centre

The Knocknagael Boar Stone

Inverness Museum and Art Gallery

The Hilton of Cadboll Stone

The Shandwick Stone

Tain and District Museum

Dingwall Museum

Strathnaver Museum

The Edderton Stone

Groam House Museum

Dunbeath Heritage Centre

The Nigg Stone

Symbols and significance

Samhlaidhean is brìgh

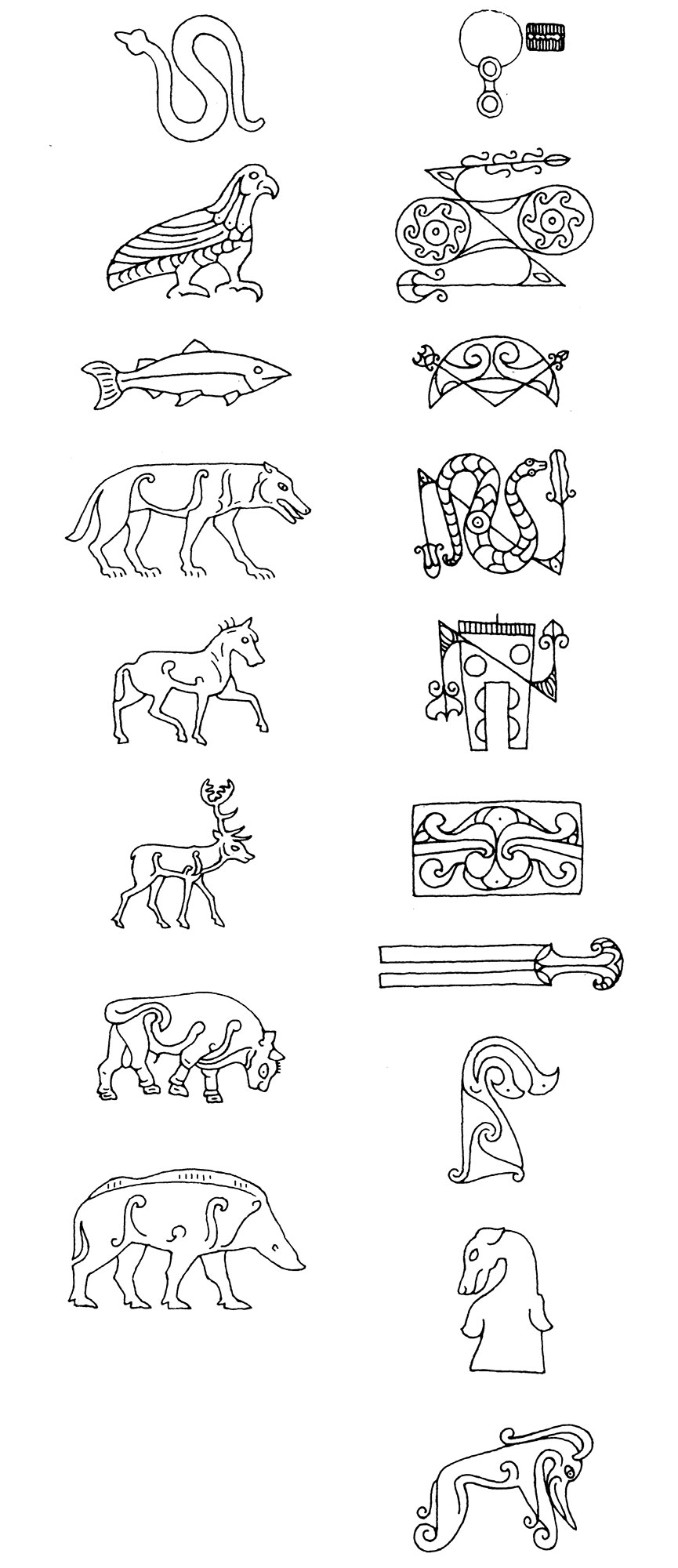

There are over two hundred stones across Scotland with some form of Pictish symbol, many scattered across the Highlands. These symbols have added to the so-called mystery around the Picts and their lives. Archaeologists and historians today are able to suggest what they meant and why the stones were put up. The symbols are quite specific in form and restricted to certain realistic animals, geometric shapes and a few everyday objects. Most of the stones have these symbols in pairs such as on The Eagle Stone, The Gairloch Stone and The Skinnet Stone at North Coast Visitor Centre. Because the symbols repeat themselves it is now generally accepted that they represent a form of codified ‘writing system’ for personal names. One theory is that the symbols represent the various clans and lineages of the Picts, with the stones showing alliances between these groups. It is also possible that the stones may have served as a record of marriage between important families or perhaps they were gravestones or territorial markers

Some Pictish stones feature specific animals such as The Knocknagael Boar Stone or the wolf from Ardross in Inverness Museum and Art Gallery. On the cross-slabs which date from a later period around the 700s AD, animals feature in royal hunting scenes, as at Hilton of Cadboll. Sometimes they are depicted as mythical beasts such as those under the cross arms of the Shandwick Stone.

The ‘Pictish beast’ is often seen as one of the strangest creatures to appear on Pictish carved stones. It is one of the most common Pictish symbols and appears on carved stones across north and south Pictish territory. Some experts think it may be a marine mammal and it has been interpreted as a dolphin or whale with water spilling from its head. The fact that all the other animal symbols that appear on Pictish carved stones are so clearly lifelike makes the strange design of the ‘Pictish beast’ intriguing.

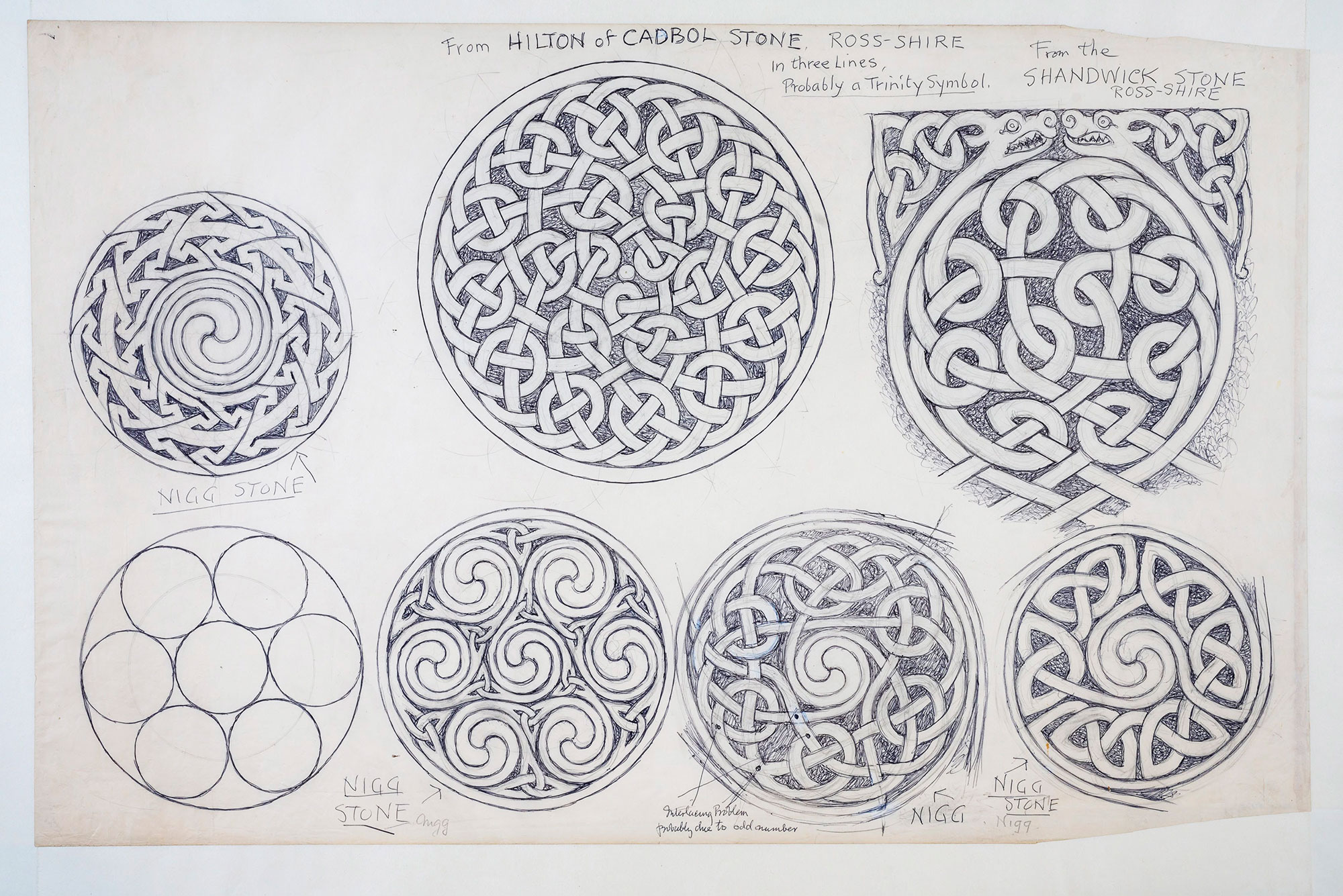

From the George Bain Collection ©Groam House Museum

Classifications and codes

Seòrsachadh is còdan

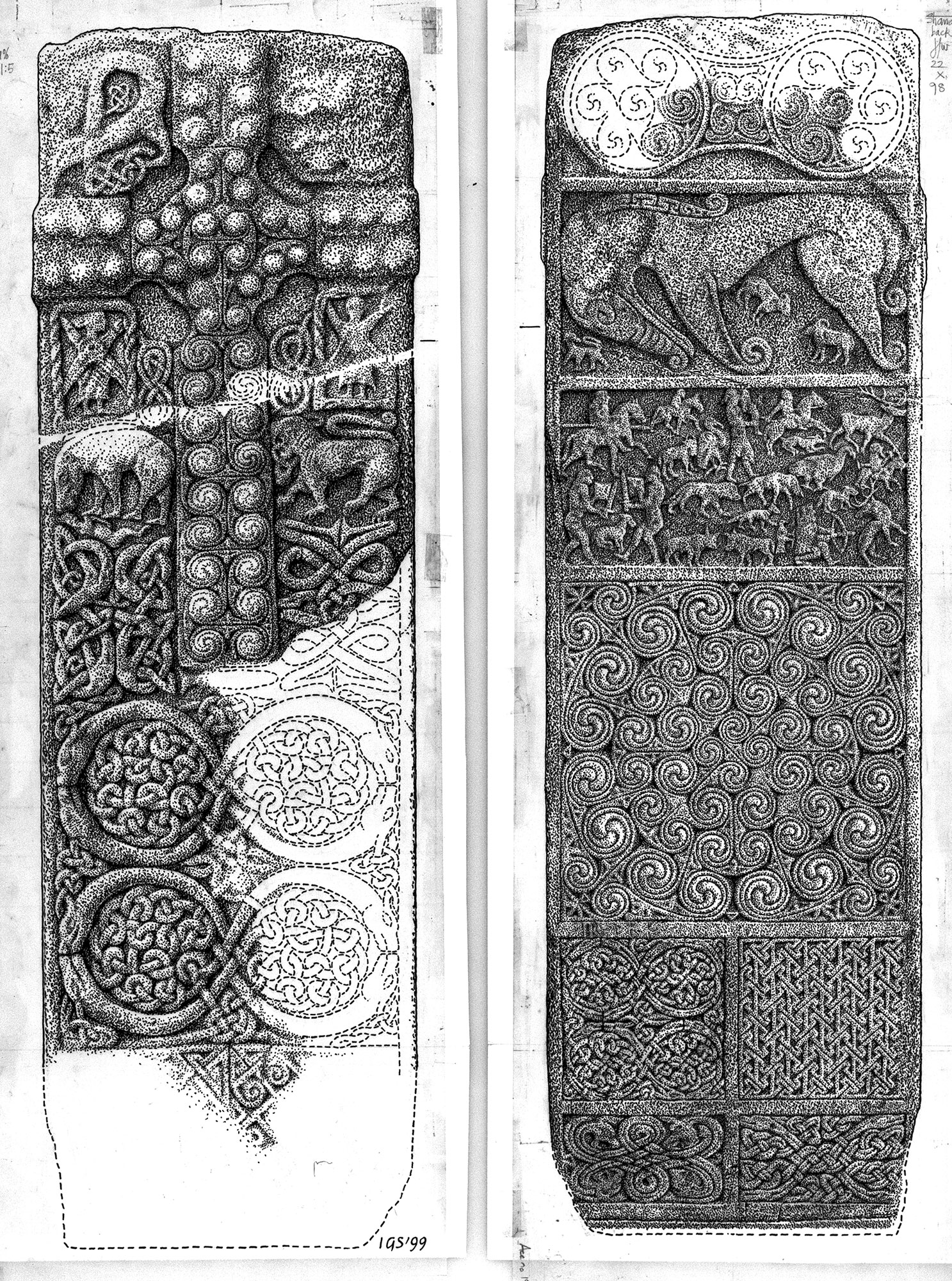

Interest in the symbols and Christian carvings on Pictish stones dates back at least to the 1700s. Antiquarians have recorded them, academics have studied them and art-historians have compared them to sculpture in other parts of the British Isles and beyond. Pictish stones are traditionally described within a structure first devised in the late 1800s by researchers J. R. Allen and J. Anderson. They created a system of classification where Class I stones have symbols incised into natural or unshaped boulders and slabs, such as The Ardjachie Stone at Tain and District Museum. These stones have no crosses.

Class II stones are carved in relief such as The Conan Stone at Dingwall Museum. The stones are prepared, or dressed, into rectangular shapes. There is always a cross on one face and paired symbols on the other. Additional sculpture may include complex geometric areas, biblical, battle or hunting scenes.

Class III stones are Christian monuments with no symbols. Some only have a Christian cross like the Farr Stone at Strathnaver Museum. Others show elements such as the impressive riders on horseback like the Edderton Stone.

Although this classification system is still used, most academics today feel that it is not helpful in building a well-rounded picture of a Pictish past. You can see Class I, II and III stones across the Highlands.

A creative culture

Cultar cruthachail

Pictish creativity was not limited to art sculpted in works of stone. The Picts were skilled metalworkers and we also have evidence of their creativity in working with bone and antler. At Inverness Museum & Art Gallery you can see the beautiful Breakachy/Erchless pendant found near Beauly and carved from shale, alongside fine examples of Pictish metalwork. Other Pictish finery has been found across the Highlands at Croy near Nairn, Rogart in Sutherland and Dunbeath in Caithness. These objects are all now in the collections of the National Museums Scotland.

Christian influences

The introduction of Christianity from around 600 AD onwards brought new images and themes to Pictish art. Much of the superb artistic craftsmanship we associate with the Picts was inspired by Christian belief. The custom of creating stone monuments remained a hugely important statement of culture and identity. Carvings became more complex, carved on both faces of specially shaped stones, with the decoration almost always in relief with the main elment being a Christian cross. The Rosemarkie Stone at Groam House Museum and the Ballachly Stone at Dunbeath Heritage Centre are good examples. But there are also stones elaborate scenes of human and animal figures such as on The Shandwick Stone or biblical stories and scenes like the Nigg Stone which shows the story of St Paul and St Anthony in the desert being brought holy bread by a raven.

Pictish cross-slabs have often been compared with pages of illuminated manuscripts like the Book of Kells and the Lindisfarne Gospels. The pages in these manuscripts have clear parallels with Pictish stones in their style of animals and interlace which are also found on some Class II stones. Several cross slabs evoke images of lavish contemporary jewellery. It is easy to imagine some of the Rosemarkie stones at Groam House Museum being decorated with gold filigree or multi-coloured enamel. The Rosemarkie cross slab looks like a book in narrow form, its elaborately decorated form resembling the sumptuous treasure bindings which survive on some Early Medieval Gospel Books. All the cross-slabs could have been covered with a thin skin of plaster and then painted, bringing vibrant colour to their surfaces. If this is the case they would have been truly spectacular.

The Breackachy Pendant ©Ewen Wetherspon (above)

Examples of Pictish Symbol Designs ©Crown Copyright HES (to the right)

Pictish art has inspired artists and craftspeople for more than a century and forms the centre of the Celtic art revival of the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. George Bain (1881-1968) was an artist and educator whose Celtic art instruction manuals have inspired countless artists and craftspeople since they were first published in 1945.

Bain was captivated by intricate Pictish stones, early medieval illuminated manuscripts and ornate metalwork from Britain and Ireland. He made detailed drawings of the designs and created a method through which they could be drawn in a series of simple steps. Bain hoped that others would use his methods to create new designs in a Celtic style to promote a uniquely Scottish national art and stimulate the rural economy. From 1945 onwards he published his methods in a series of popular instruction manuals that continue to inspire artists and craftspeople. Today, his instruction manuals are still in print as Celtic Art: The Methods of Construction.

The George Bain Collection is cared for by Groam House Museum and is a Recognised Collection of National Significance to Scotland. It contains Bain’s sketches, hand-drawn plates for his books, designs for craftwork and craftwork itself – carpets, leatherwork, woodwork, embroideries and ceramics. The Collection provides a unique insight into George Bain’s working methods, his teaching and advocacy for Celtic art, the impact of his publications, and the ways in which his domestic life reflected his commitment to and philosophy of Celtic art.