Pictish lives

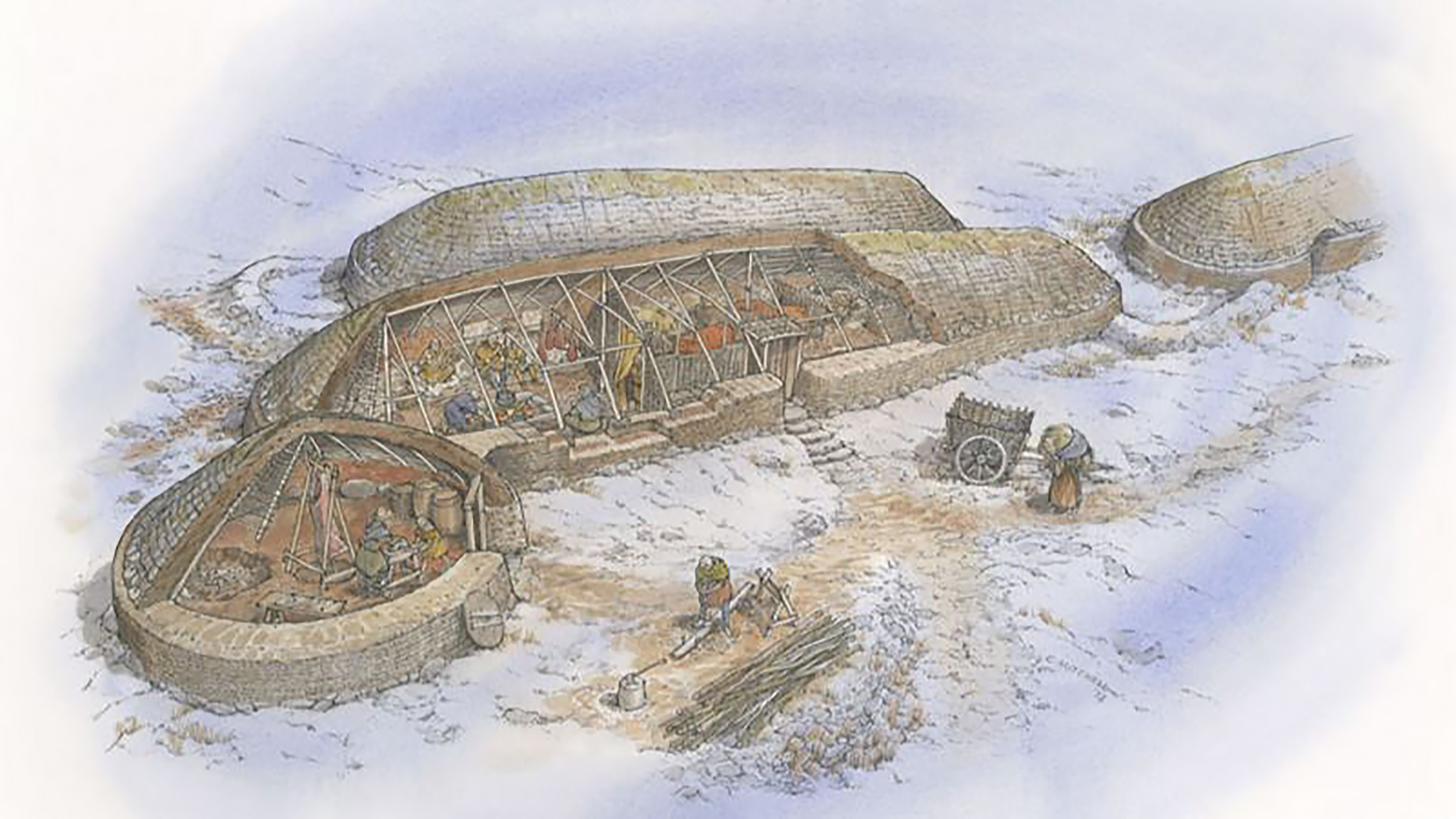

Reconstruction of a Pictish homestead in Glenshee ©Chris Mitchell

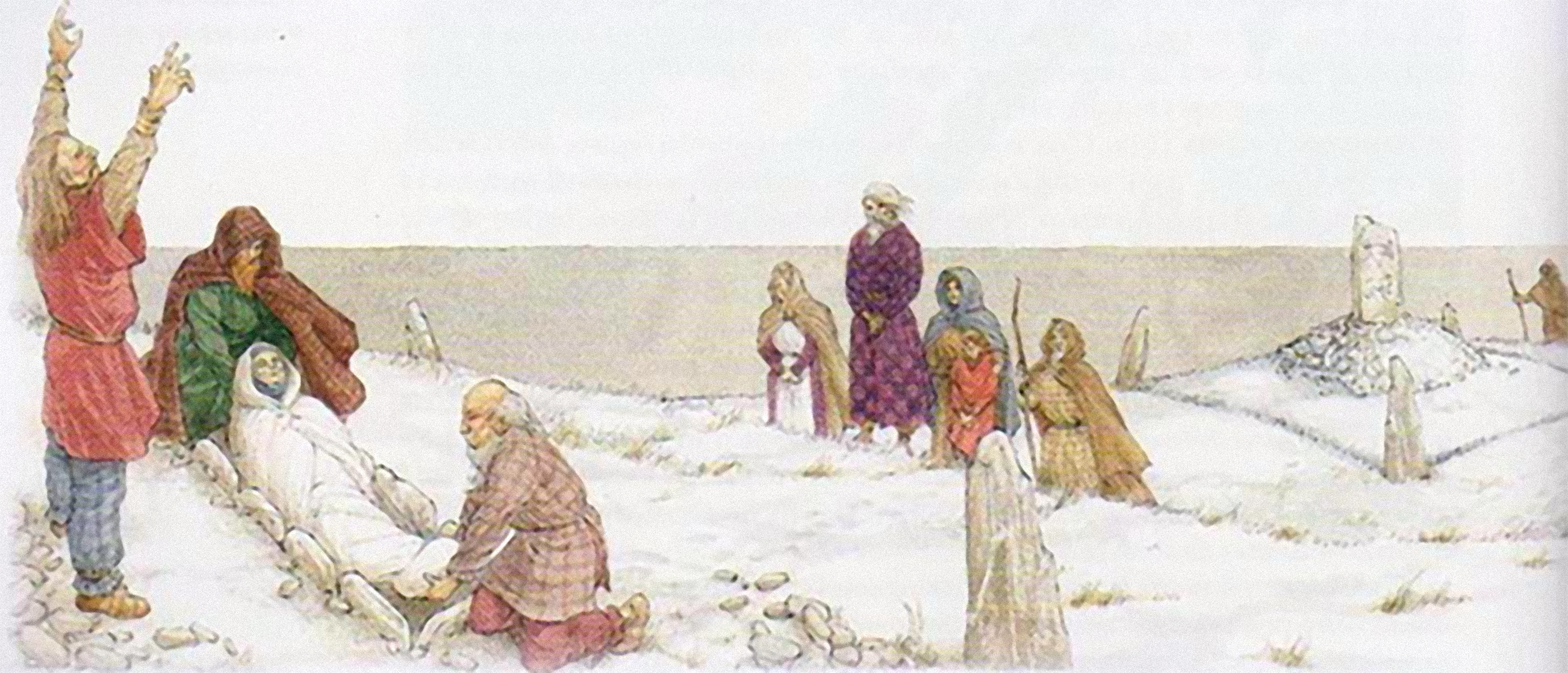

Artist’s impression of a Pictish burial ©Mike Moore

Pictish lives

Beathannan Cruithneach

Casting new light on Pictish life

A’ soillseachadh beatha nan Cruithneach às ùr

Dunrobin Castle

Clach Biorach

The Dingwall Stone

Inverness Museum and Art Gallery

The Hilton of Cadboll Stone

North Coast Visitor Centre

Craig Phadrig

Kyle of Sutherland Heritage Centre

Dingwall Museum

By their own name

Fon ainm fhèin

Roman historians and poets were the first to name the Picts, describing them as ‘Picti’. What they meant is still much debated, but most agree that it simply meant ‘painted people’. This does not mean that the Picts called themselves by this name, or even that there was any long-lived coalition of tribes or groups who identified themselves as a single people.

‘They tattoo their bodies with coloured designs and drawings of all kinds of animals; for this reason they do not wear clothes, which would conceal the decoration on their bodies’.

Herodian in ‘Roman History’, third century AD

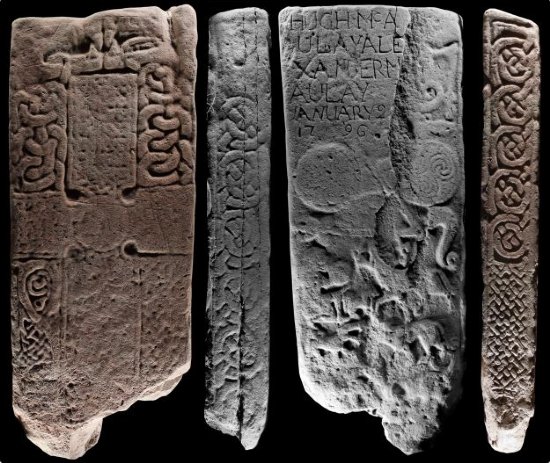

The only surviving Pictish alphabetic writings are short inscriptions on stones which are carved in ogham or Roman script. Ogham is the earliest form of writing found in Scotland – it originated in Ireland and dates to the 300s AD, with each letter represented by a mark along a central line. Those that can be translated always include one or more personal names such as on one of the cross slabs at Dunrobin Castle Museum. Some names written on carved stones also appear in the king-list manuscripts drawn together in Ireland to show the kings ‘of Picts’ and kings ‘of Fortriu’ from the 600s to the 800s AD. However, understanding these king-lists is not easy and they should not be considered as completely trustworthy as some of the earliest entries may have been added several hundred years later to suggest a history of royal succession which may not have been accurate.

Other second-hand references to Pictish battles, warlords and even peasants are mentioned in chronicles and biographies written by scribes from Ireland, Northumbria and further afield. Bede was an Anglian monk based at Jarrow in Northumberland in the 700s AD. His texts concentrate on stories of successful conversion of the people of the British Isles to Christianity but also include details about people’s lives, including the Picts. Most people were farmers or worked on farms and very few had any say in running things; slavery was common. They had cows, sheep, goats and pigs but they also hunted deer and seals on the coast.

Memorials to the dead

Cuimhneachain do na mairbh

The Picts were like other cultures in having other beliefs before they were introduced to Christianity. Some of the early symbol stone carved stone sites were possibly special or sacred places and there is evidence that some stones were placed near to, or on top of, older sites. In some places prehistoric standing stones were carved with Pictish symbols, for example at Clach Biorach.

The Picts had different ways of burying or disposing of their dead. Remains that can still be found in the landscape include cremations, simple burials in the ground or in long cists (coffins made of stone) burials, burials under cairns, and burials under round and square barrows (mounds of soil or stones). Some remains may also have been left out in the open to decay prior to burial, perhaps with the flesh and organs removed. Symbol stones have been found connected with some of these burial sites, such as the Dairy Park Stone at Dunrobin Castle Museum and the Garbeg stone at Inverness Museum and Art Gallery. Several Highland burial sites feature impressive upstanding remains; at Garbeg, Drumnadrochit and at Whitebridge in Stratherrick. Round and square type ditched barrows appear alongside each other at both Garbeg and Whitebridge – a feature thought to be unique to the Pictish cemeteries. This blog https://nosasblog.wordpress.com/2014/10/12/pictish-burial-practices-and-remains/ gives further information.

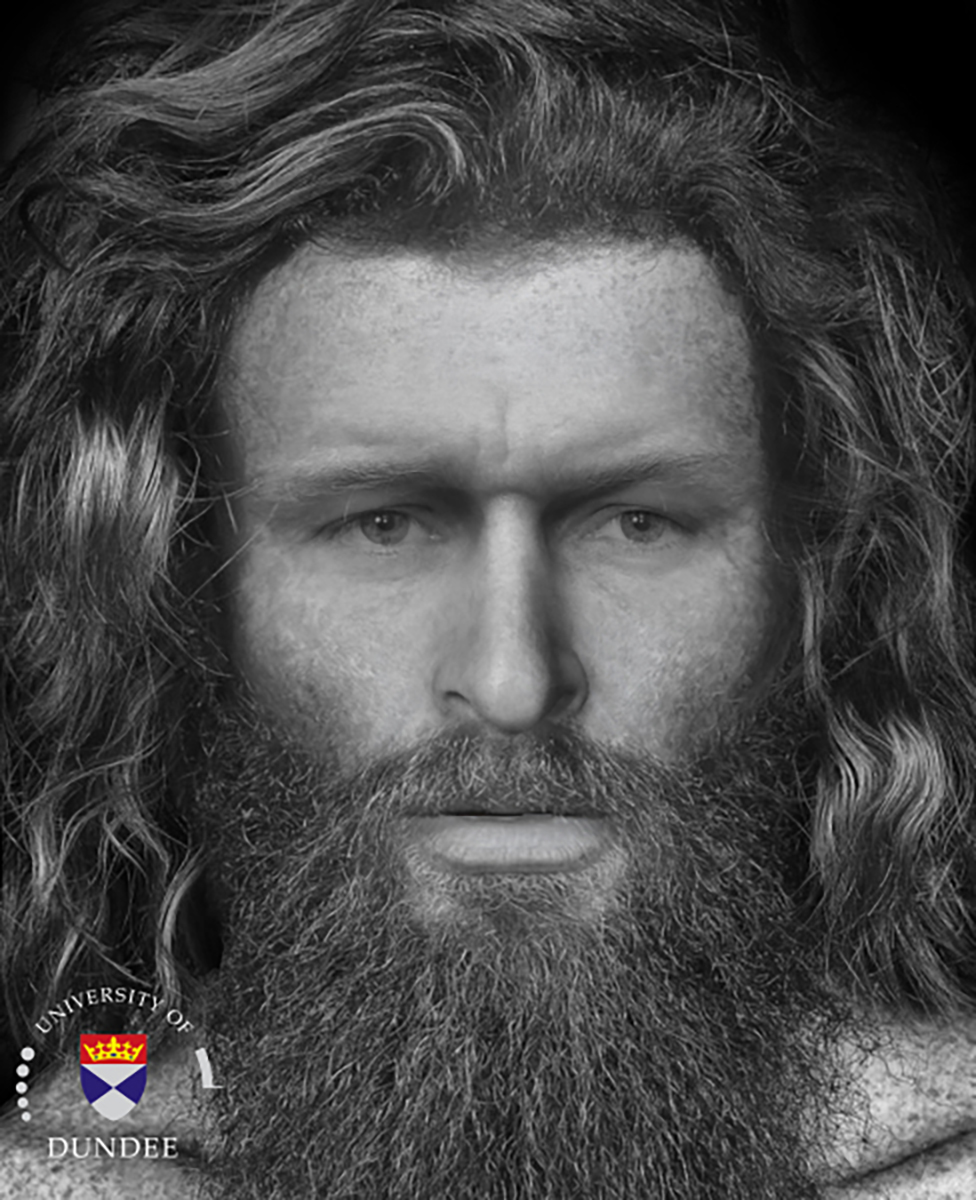

Rosemarkie man

Fear Ros Mhaircnidh

In 2016, archaeology excavations in a coastal cave at Rosemarkie on the Black Isle made the remarkable discovery of a skeleton dating to the Pictish period sometime between 430 and 630 AD. This well preserved and almost complete skeleton was especially significant. Analysis showed that ‘Rosemarkie Man’ was probably in his early thirties, powerfully built and healthy when he died. He had a high-protein diet suggesting he ate foods enjoyed by people of high status. However, evidence of five separate severe facial and cranial traumas showed the man suffered a brutal death.

The body was buried in an alcove in the back of the cave. The unusual positioning of the body with boulders and butchered animal placed over the top, may indicate a particular significance to this individual and to his death. The cave burial could have been a way to ritually place his body at an ‘entrance to the underworld’. With more to discover, ‘Rosemarkie Man’ may still offer up secrets of Pictish life and society in the Highlands. https://nosasblog.wordpress.com/2017/02/19/introducing-rosemarkie-man-a-pictish-period-cave-burial-on-the-black-isle/

A people’s past

Àm nan daoine a dh’fhalbh

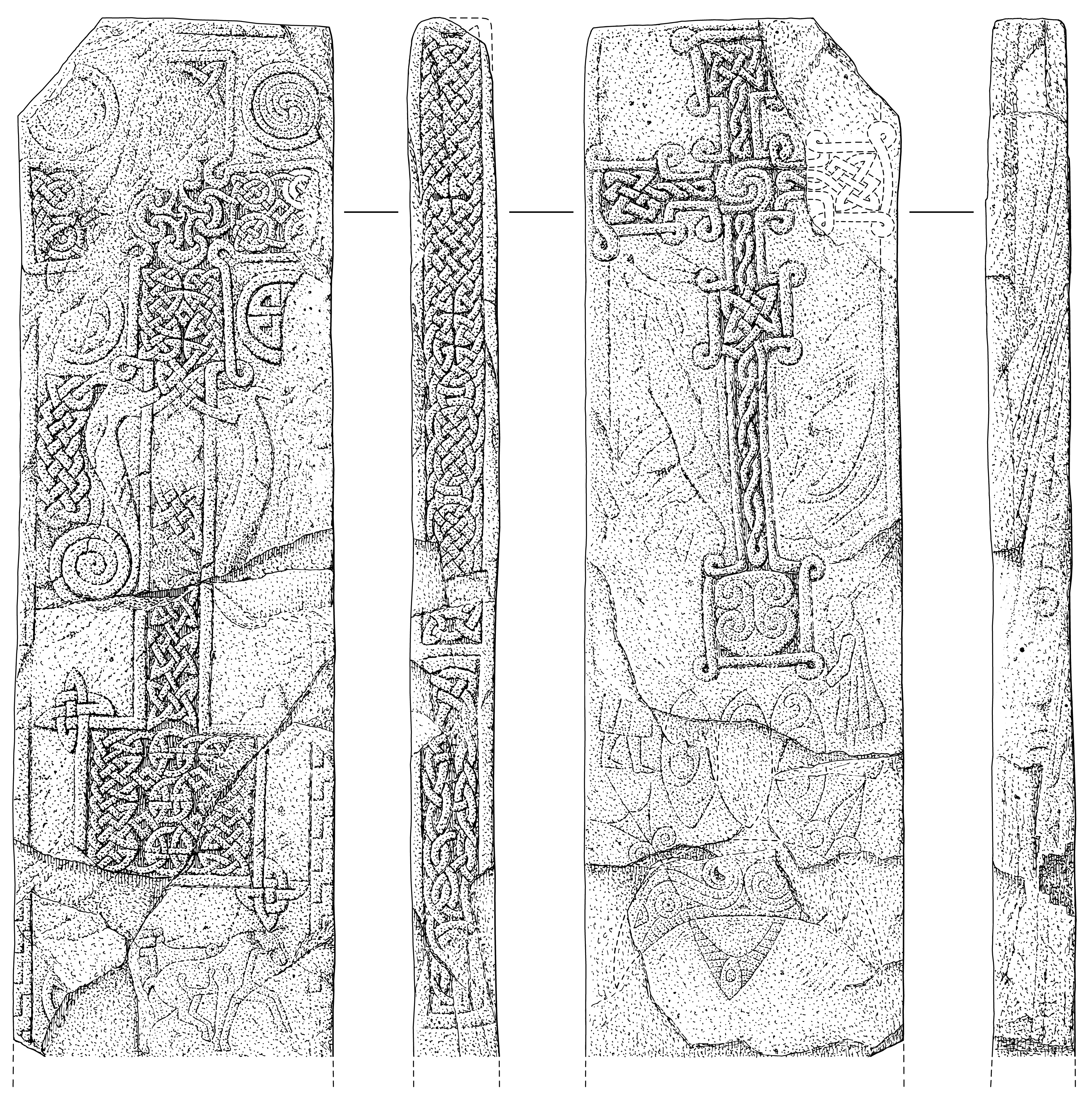

The Skinnet Stone at Caithness Horizons also gives us a tantalising glimpse into Pictish life. It is one of only three known Pictish stones with an image of a Pictish horse-drawn vehicle. Incised at the foot of the cross there are a pair of horses harnessed to a light wagon or chariot. As horses were not used as draught animals in farming at this period, they must be pulling a carriage. A pair of hands holding the reins of the carriage is just about visible. Two symbols on the other side of the stone sit below the decorated cross set on a square base. It is very tempting to associate these with the aristocratic image of the horses on the other side, particularly given the possibility that the symbols are associated with people’s names. Perhaps the symbols spell out the name of the person who may once have been in the chariot or wagon.

Homes and hillforts

Dachaighean is dùin-chnuic

Hillforts were important defensive and symbolic sites, centres of power and prestige. They were located in prominent positions close to important trade or communication routes. Craig Phadrig, which overlooks the Great Glen and the Beauly Firth, was first built in the 300s or 400s BC but re-occupied by the Picts around 500 to 700 AD, and excavations undertaken in 1971 revealed artefacts from the Pictish period. Perhaps the site was home to Pictish kings. Today the area has been planted with trees but at the top, the ramparts and fort interior are easy to see, and the expansive views from the fort to the west, north and south suggest why this site was chosen. Evidence of the homes and lives of ordinary people is harder to find. Timber buildings probably existed but no visible evidence remains and the discovery of settlements across arable lands relies on aerial photography.

Place-names

Ainmean-àite

The Picts have left their legacy in placenames across northern Scotland although understanding these can be a challenge. Names such as Pitlochry, Pitmeddon and Pitcarmick are thought to have a Pictish connection. The ‘Pit’ refers to a piece of land and the second element is a personal name or descriptive term. Pitkerrald near Drumnadrochit means ‘Place of Cairell’ and Pityoulish near Aviemore means ‘Loch of the settlement of the bright place’. Similarly, placenames that begin with ‘Aber’ like Aberdeen, Aberarder or Abriachan meaning ‘river mouth’ may be Pictish in origin. The term ‘carden’ also has Pictish links as in the Kincardine Gravemarker, and nearby Migdale is thought to take its name from the Pictish word ‘mig’ (bog or marsh). See https://cairngorms.co.uk/uploads/documents/Learn/Learning_Projects/SimonTaylorPictishPresn.pdf for more information.

Portmahomack – excavating the Calf Stone

Illuminating archaeology

A’ soilleireachadh arc-eòlas

Archaeology allows glimpses of ways of life that other studies cannot provide. Ploughing, building work and archaeological excavations sometimes result in the discovery of new Pictish stones or objects and can help us in the understanding of sites.

The recent discovery of the Conan Stone, now on display at Dingwall Museum has helped to prove the prevalence of Pictish settlement in the Conon Bridge area of Easter Ross. This is supported by discoveries of a Pictish brooch pin and a symbol stone fragment, both now on display at Inverness Museum & Art Gallery.

Slightly further north, large-scale excavations at Portmahomack revealed the existence of an important monastic site which is significant in national and international terms.

All too few Pictish sites have been found or investigated meaning that there are still considerable gaps in our knowledge. However, the progress made in recent years has been impressive and has changed many views on the Highland Picts. It shows that the Highlands, far from being a northern outpost of a southern Pictish kingdom, was an important centre of Pictish power in its own right. The University of Aberdeen’s Northern Picts project is making exciting discoveries about the lives of more ‘ordinary’ Pictish people. The University of the Highlands and Islands’ Institute of Northern Studies is carrying out ground-breaking historical research, while experimental archaeology projects and accidental archaeological finds are also helping to shed further light on the Pictish past.