An introduction to the Picts.

Dr Oisín Plumb, Institute for Northern Studies, UHI

The earliest surviving reference to the Picts comes in a Roman text written around AD 297. From that point onwards, there are a number of references in Roman texts to Picti. This word might mean the ‘painted people’ and, though there is no firm evidence of the tattoos or body paint often imagined in modern times, it is far from impossible that this is something that these earliest ‘Picts’ were known for. There is no evidence that this new name reflected the arrival of a new group of people. In fact, some of the same names for places and local population groups are recorded both before and after the term Picti came to be applied to them. What seems to have changed was the need for a new term to differentiate those who lived within (and just next to) the boundaries of the Roman Empire (the Britanni), and those who lived further beyond it.

By the early medieval period, a Pictish kingdom had emerged which was a significant player in the cultural and political affairs of Britain and Ireland. At its height, it encompassed most of the land north of the Forth and Clyde. It’s hard to say to what extent some parts of the far north and west (such as the North-West Highlands, the Western Isles and Shetland) were firmly within the kingdom. However, in all these places, the existence of artefacts bearing Pictish symbols (more on the symbols shortly!) attests at least some amount of engagement with Pictish culture.

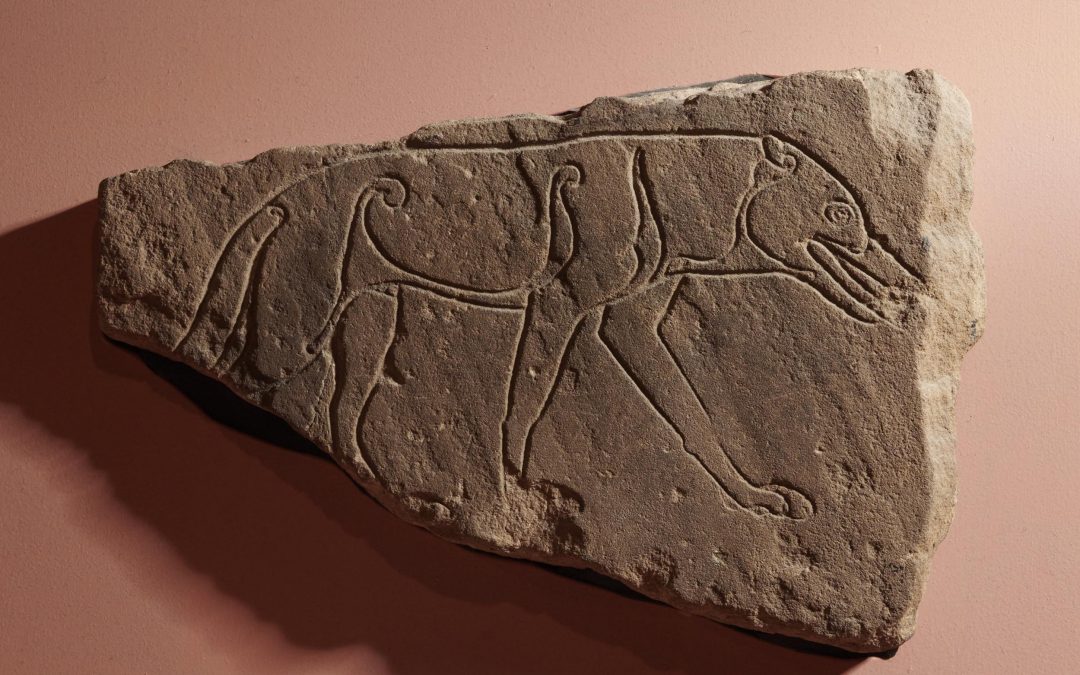

The Pictish kingdom does not seem to have been quite as fragmented as some other places at the time. In Ireland there were hundreds of local kings at any given time, with clusters of these kings ruled by an overking, who were in turn ruled by fluctuating numbers of regional or provincial kings. In contrast, only three Pictish regions with any kind of local king are mentioned: there is a single reference in our sources to a king of Atholl and a reference to an under-king of Orkney. However, there are many references to the kings of Fortriu. This seems have been by far the most powerful Pictish province for much of the history of the Pictish kingdom. Very often, kings of Fortriu were also considered to be kings of the Picts. Most scholars now agree that Fortriu was located in the North of the Pictish kingdom, centred on the area around the shores of the Moray Firth. Evidence of the importance of the area includes the great range of symbol stones found throughout the northern Highlands. You can see tremendous examples of these at many of the sites you visit along the Pictish Trail. There is still debate over the purpose of these monuments. Suggestions include that they might have been used to mark territory, to commemorate alliances or marriages, or to commemorate the dead. The same symbols are found over the entire Pictish area from Fife to Shetland. The symbols usually come in pairs, with some exceptions: The ‘mirror’ and ‘mirror and comb’ symbols usually get placed alongside another pair of symbols. The beautiful mammal symbols, such as bulls, wolves and bears, are often carved on their own [fig, 1]. Some Pictish symbol stones, known as Class I stones, feature only the symbols [fig.2]. Class II stones are more highly decorated, featuring a large cross and other ornate decorations besides the Pictish symbols [fig. 3]. There is still debate over whether or not the earliest Class I stones might pre-date the coming of Christianity to the Picts. However, the presence of the symbols on the overtly Christian Class II monuments shows that at the very least they were not seen as being incompatible with Christianity. Although we still don’t know for certain the meaning behind the Pictish symbols, these monuments can give us a great deal of insight into Pictish culture and society. Stylistic features of the monuments demonstrate artistic links between the Picts, the Gaelic world (both Ireland and Dalriada in the west of what is now Scotland), and the Anglo-Saxon world- particularly Northumbria. Links with other places were made possible by the good connections that the north of the Pictish kingdom had to other territories. For example, the Great Glen provided a direct route to the Gaelic speaking kingdom of Dalriada, and in particular the great monastery of Iona. The sea provided links with Northumbria, and other places further afield.

Although no Pictish books survive, there is evidence for book production at the monastery of Portmahomack, suggesting that this was a great centre for learning. Using place names and Pictish personal names which have survived, it seems likely that the Pictish language was closely related to the ‘P-Celtic’ British language (the language which was to become modern Welsh). However, it is also possible that there was some amount of ‘Q-Celtic’ influence (Q–Celtic is the language branch which includes modern Scottish Gaelic and Irish). This might have resulted in a gradual transition from a more ‘P–Celtic’ language to fully ‘Q–Celtic’ Gaelic over time.

By AD 900, contemporary sources stop referring to a Pictish kingdom, and instead refer to a territory known as ‘Alba’. There is still no agreement over how and why this transition occurred. This was a time of great upheaval, not least due to Norse invaders. Close links between Pictish and Gaelic elites may have played a part in a joining of cultures. At this time the use of Pictish symbols on sculpture came to an end. The Pictish language also seems to have been entirely replaced with Gaelic around this time, though the timescale for this is much less certain. Whatever the reasons for the end of the Pictish kingdom, what remains is a fascinating legacy of incredible monuments which can still be seen today throughout the Pictish Trail.

Figs:

- Wolf, Inverness Museum and Art Gallery

- Class I symbol stones in the Dunrobin Castle museum

- Class II symbol stones, Caithness Horizons