Helen Mackay tells us the story of the Crosskirk stone.

This is a story about a symbol stone that was the centre of its world. It stood beside a large broch on the far northern shore of mainland Pictland, a little to the west of Thurso, at a place today called Crosskirk. Until one day the people closed down the broch, and the stone stood for the best part of two thousand years, alone, on the edge of the land, with the sea crashing on the cliffs below. The stone was eventually lost, so we can’t see it today, but we can still stand where it once stood, and watch the wild sea below, breath the salt wind.

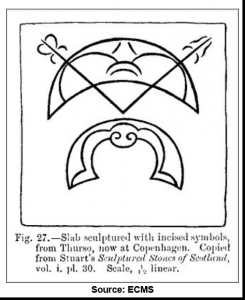

A sketch of the Crosskirk Class I symbol stone

The symbol stone

Fortunately, before it was lost, a sketch of the symbol stone was made. Two symbols, a crescent/Vrod and an arch with a protuberance inside the top curve. The crescent/V is the most common symbol, 1 in 5 of all symbols. The arch is also relatively common, found widely over Pictland. But the arch symbol must have had a particularly important pagan meaning, as it doesn’t occur on Christian stones, with one possible exception at Eassie which is too eroded to be sure.

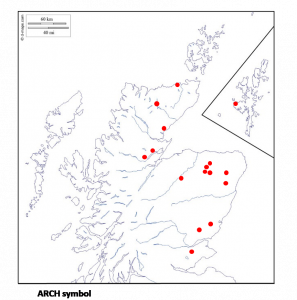

What does the arch mean? Perhaps the sky itself, or the rainbow, or a bridge between shores, perhaps even a cave, a real arch? Perhaps many of these things at the same time. Perhaps as the sky it was the symbol of the Dagda, the great sky father. But we have a lot of work to do before we can say for sure.

Map of arch symbol locations

The broch, the stone and its people

The broch where this symbol stone stood was a hive of activity in its day, around 400 BC to 250 AD. The people who lived here in the small settlement nestled around the broch’s foot, ground grain, spun and weaved, made leather and sewed clothes, wore bronze spiral rings. They ate mostly sheep, kept cows for dairy products, and hunted wild boar and deer. Their broch had a deep well for fresh water. Although on the far northern shore, the people knew of the wider world, and despite the distance, Roman glass ornaments and Samian pottery found their way here from across the Roman world. And, the broch people carved a beautiful symbol stone for their own place. They were wealthy, connected, thriving.

Crosskirk lies beside a tiny inlet on the north coast of Scotland, a few miles to the west of the big bay of Thurso. The people only had rowing boats, some perhaps with a sail, and the passage to Orkney was arduous and dangerous. Knowledge of the strong tides and ocean streams was critical for a safe passage, and perhaps some of these people acted as pilots for boats crossing to Orkney. The currents and winds offered only a short window for the passage, it was easier to row to and from Crosskirk rather than Thurso bay (as we saw on a modern attempt to row across in a replica boat). Crosskirk’s symbol stone was a place to ask the gods for protection on the voyage, and to thank them for safety on arrival.

Map of Pentland Firth sea passage Crosskirk – Orkney

The disaster and the watcher

But then, around 200 AD, something dire happened, and brochs all over the land were closed down. What happened to trigger this reaction we don’t know for sure, but the population of Scotland seems to have dropped precipitously, possibly the result of diseases introduced from the Roman empire. But brochs weren’t just deserted, they were closed with complex rituals, and sometimes this involved burying a significant deposit near the entrance to the broch. Just outside the entrance to the Crosskirk broch, a burial took place, a really exceptional burial – a person was buried in a cist lined with large slabs, and here’s the strange thing, they were placed sitting upright, with a large upright slab at their back, as though to watch and guard. We hear stories of great warriors being buried upright to continue to guard the land in death as they have in life, and here we have a person watching and guarding for all of time to come.

Seated burial at the entrance to the broch

This guardian would watch through the years. His people would be prosperous at times, riven with plague and grief at other moments. After a few centuries, a new religion moved across the land, and people would sing new songs and come on pilgrimage to the healing well. Then the Norse people arrived in long boats and settled in the area, soon becoming a seamless part of the watcher’s land. A millennium into the watcher’s vigil, a small chapel was built within a few steps of the watcher. Through time, the wind would howl in storms and the pounding sea eat away at the cliff below the broch. The chapel was rebuilt in stone, then eventually deserted. Grievously sad, he witnessed most of his people being driven away off their land, to such far off places he couldn’t have dreamed of. Still he watched.

Until one day, the archaeologists found him and released him from his guardianship. They studied the broch, then decided it was now too dangerous to leave on the crumbling cliff edge and pushed the whole thing into the sea below. The symbol stone was uplifted and made a present of to the King of Denmark, who then lost it. And so things end. But the guardian had watched for nearly 2000 years, job well done mate.

Further reading

The Crosskirk symbol stone: https://canmore.org.uk/site/319016/crosskirk

The Crosskirk broch: https://canmore.org.uk/site/8019/crosskirk